Original Article was written by Bob Belinoff himself:

https://medium.com/@bobbelinoff/a-film-maker-makes-seventy-29c48f9b4e7e

I decided to make a movie like a writer would write a book. In a corner, at a desk under a window.

I had been making documentary films for 30 years. For advertising agencies, institutions and causes. We had a production company, it was a going concern. We had a crew. We had a back room full of production equipment. We had clients. We delivered the product. But now at the age of seventy, I wanted to try something else.

I wanted to make a short movie like a writer writes a short story. Alone.

So I closed the door on our production office, taught myself enough editing to get by and called in a life time of experience in story telling and the commercial visual arts. Given the changes in technology and the film production model I knew it might be possible to undertake this multi-tasked journey from idea to screen, without editors, shooters, advisors, specialists or crew. Solo.

New online distribution platforms gave me easy access to screens, at least small ones. Editing software was increasingly glitch-free and no longer required the mind of an engineer or code writer to use. The cameras were so consumer friendly they seemed to run by themselves. The images, music and effects, all available online, made it possible to redefine what it meant to be a filmmaker. It was possible to become writer, director, shooter, art director, designer, gaffer, goffer, actor, marketer and distributor all rolled into one. And you could, if you wanted, make a film like writers write books. Alone, at a desk. News to me. I had just turned seventy years old what did I know?

Turning seventy had been a suitably traumatic experience, so I thought I would make a film about that. And I would make the film by myself. No team, no coordination no calls at night. I was through with teamwork. I would work alone. This was to present some challenges but onward I charged.

Film making, as I previously practiced it, had been a group activity. And the arena in which we film-makers work is called a community — a film community — for a reason. There are many disciplines involved in putting together a film, some technical, some social, some aesthetic. Each requiring a different part of the brain, a distinct temperament, and technical ability. And not a few of the disciplines required are logistical; budgets and schedules have to be adhered to, not to mention food, lodging, transportation, the movement and maintenance of equipment and the storing and cataloguing of footage — all this while adhering to some kind of vision of the final product and keeping track of the 10,000 tiny technical events that go into knitting this vision together out of thin air.

The adventure begins.

I wanted, as I say, something of a solo artistic adventure. My task, as I had made films for clients was as a writer, producer and, occasionally, a shooter. But films are really made at the editor’s bench. And although not officially an editor I had sat with a great editor for many years, and in the process, I learned what editing software could do. By the time I closed up shop and retreated to the seclusion of my home office I had taught myself enough, using Adobe Premiere software to hopefully edit a film myself on an iMac.

Adobe Premiere was not easy for me and we would soon part ways, but its a good idea to start where you are – and Adobe Premiere was what we had in the shop. So thats what I started with. Now I barely have the technical ability to open a jar of apple sauce. I knew if I were going to make a film, by myself, by hand, a simple intuitive editing system would be needed and I would have to love using it. For me, a low tech film-maker if ever there was one, this relationship with editing software would have to be a love affair.

As you might expect, Adobe Premiere was not kind to me and early on the marriage fell apart. We were, as I knew, ill suited for each other. Adobe is very logical and left brain with, it seemed to me, many numbers and very small type. My brain barely registers numbers and most times only the right side is fully functional. I can only learn from experience, making mistakes is my creative process and I found Adobe less playful and somewhat unforgiving. Whats more, it updated frequently and my learning curve, always steep, was making me dizzy. I could not work with it. I wanted to paint. Adobe Premiere, for me, was like working with surgical tools.

Then, after resisting it for years, I started a flirtation and then a full-fledged relationship with Apple’s Final Cut X editing software. Suddenly the sun came out, it was all singing and dancing. I loved it. I divorced Adobe and indiscriminating film maker than I am, I simply started shooting things (any things), loading clips into my computer and playing with Final Cut X. I had no idea what I was doing or where this was headed. This was exactly where I wanted to be. The bottom line; I could make this work. With FCP X I could make a film completely by myself.

Early on I realized that working alone would present me with some problems. By going solo I was not only sealing myself off from clients, but from friends, compatriots and other professionals; a whole world of discreet technical or artistic expertise as well as travel and sociability — all of which had been connected to my assignments and my team. Whats more I myself seemed to be in retreat from the film industry, an industry, based on a social arena; a performing troupe and a willing audience.

Making a film by yourself necessarily backs you into a somewhat isolated corner as does simply getting older. Somewhere in route to the age of seventy-one begins to become invisible. In film work, we call this a slow dissolve. You just appear to fade. Maybe its the constantly changing technology. Maybe its the beautiful and ever-present youthful fervor among young film-makers but what happens is this; you not only retire but you are -in fact- retired from the scene. While I wanted to work alone, I wasn’t really prepared for just how isolating getting older in a young person’s field — and no real arena to play in — would be.

You have few social discoveries to make in your 7th decade, you aren’t out much, and when you are everyone is younger and you have less to learn. So there I was, home alone. Fine. I would explore my inner landscape. Obsessive diarist and doodler that I am, self-exploration was a natural for me. But I learned I needed to practice it, at least in some part, away from the desk and out in the real world. Its nice to have somewhere to be and something to actually “do” while trekking around in your own inner angst. And so in the process of making this film I developed a scaffold on which to build a relationship with both the outside world and myself.

For example, once I began shooting the film I might find myself on location, so to speak, at my local Barnes and Noble with my little low profile Sony NEX at my side. I might stash it on a bookshelf, turn it on, walk to the front of the store come back, do a jig in front of the camera, record a scene, pack up and get out. Sometimes buy a book. This felt like an especially productive and entertaining way to be in a bookstore. I would end up doing this at supermarkets, on highways, in trains and while visiting friends in distant cities. I could both work alone and get out in the world – as long as I had a tripod, but more about that later.

The fact is at age seventy I was in fine fettle. I could, possibly, work creatively for another fifteen or twenty years. Thats a whole lifetime. What else was one to do? I had just been kidnapped by a depressing presidential campaign for a year and I wanted little to do with the daily news and a world in disarray. What was most exciting to me was my own vision, my inner world, how I saw things, using my stuff, whatever gifts I’d been given, and using them up completely.

I couldn’t tell where the outside world was going, but inside I was making progress. I was putting something together. I have always been fascinated by the way words and images worked with each other and was reasonably facile in manipulating both. Now I had some word and image manipulating machinery, lets see what happens.

The script and how to forget about it.

We have a guest house on our homestead outside of Albuquerque, New Mexico. I took refuge in a corner of it and locked myself in for two weeks with paper, pen, laptop and a dozen of my favorite books for inspiration. I wanted to write a script and create something that friends, people I knew could relate to. Granted there was a certain amount of reaching out in my process. “Hey!”, I wanted to say to both myself and the world — “I’m still here”. Having disappeared from the scene I wanted to communicate as much as I could with some of the cast. But mainly I just wanted to use myself. I had to make something.

I knew my film would need to be short. That would keep it simple for me and I knew people would likely watch it on a smart phone or a tablet where the average attention span for video is about two minutes. But my story was going to be longer than that, so I decided to tell it in episodes of under two minutes each.

Because I knew sound could be an issue on mobile devices I wanted to keep dialogue and exposition of any kind to a minimum. Also I didn’t want to mess with recording dialogue or use any sound equipment, which I didn’t trust myself operating anyway. I would use the built-in mic on the camera whenever I could.

I wanted this to be visually involving, but I wasn’t much more proficient with a camera than I was with sound equipment. I couldn’t pull off any really stunning shots, and I didn’t want to. What had taken master photographers decades to learn was now built into camera settings making everyone an apparent soft focus genius. None of those creamy, beautiful images for me. I was a writer, and I liked it rough. I would keep the camera on its flattest, most basic automatic settings.

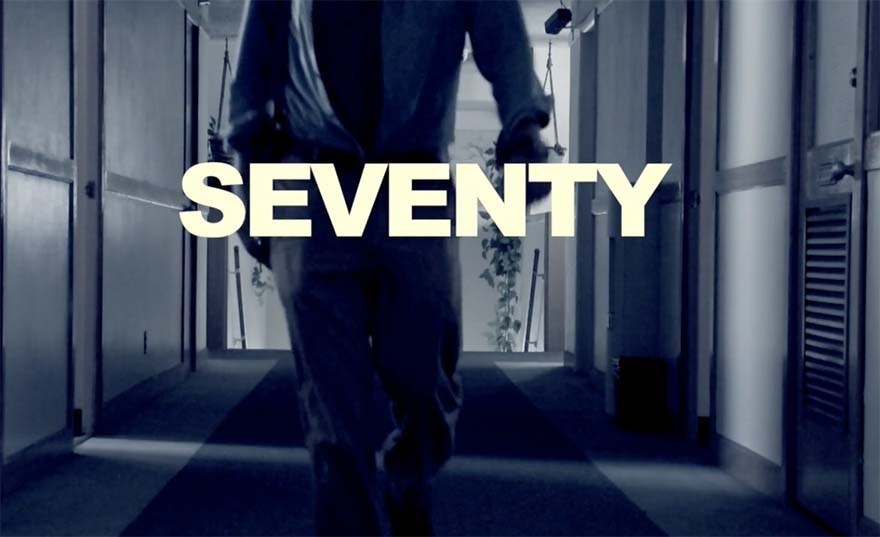

I saw “Seventy” as an episodic story with each episode having a bit of a cliff hanger ending. And I wanted to be light, no heavy existential turmoil. The world needed smiles.

In the process of producing my mini-epic, as I say, I didn’t want any meetings, budgets, clients or objectives to live up to. I didn’t even want a partner or a crew. I just wanted a bit of an adventure.

I walked out of the guesthouse after two weeks with a script in five acts based on what I had done since I closed up my production business; a bit of distraction, some travel, soul searching, etc. Then I threw the script away. What was left degenerated into a vague outline in my mind? I wanted my thinking to leave a misty impression not a shot by shot script. And things got increasingly vague as I went, not sharper. I wanted to be open to serendipity and chance, I wanted starting points only. I was creating something that didn’t exist, not painting by numbers. This was to be an exercise in my own ability to let go. I would, using only my own judgment, discernment if you will, follow where the work wanted to take me. Flexibility and vagueness were crucial.

I took endless notes, gave them to myself and headed into production. In the morning I would meet with myself and all of my team mates; lighting, costume, script, camera, sound — me, me, me and me. I had hesitated to use a tripod in our corporate work even for interviews. Now, since I had no camera person, I couldn’t make the movie without it. And I ended up liking the steady shots, they were symmetrical, had a visual beat and you could cut to them.

I was the lead, indeed the only actor. I directed myself, reviewed “takes” with myself and, after turning the camera on, ran around to the front of it for endless re-shoots and pickups. Later I sat with my editor and writer, me and me. No meetings, no call sheets, no urgent texts, no hard feelings, no nothing.

And all the while — between production phases, writing, shooting, editing— I was reading about old masters; painters, musicians and writers and what they were doing in the later part of their lives. While I was making the movie I started figuring out what being an artist might be like. An artist, whatever that was, was something I always wanted to be.

The film, was driving, I was just along for the ride. I went where it wanted me to go. And I could tell from feedback from various friends from my other film-making life that what I had was good. I would create a draft of an episode, send it out, and the reviews were encouraging… “well what happens, this is great, send me more,” people would say. I had an audience and I soldiered on with new episodes.

I read and re-read James Hillman’s “The Soul’s Code”. Hillman is the astute and delightful Jungian Psychiatrist who postulated what he called the “Acorn Theory”; there is an innate part of us that exists in us from birth, even before birth…it calls out to be lived. And our job is to listen to it, find it and follow it. Forever.

I wanted to say something about this Acorn Theory and I wanted to say something about art, craft, technology and the new tools of creative production. But I didn’t want to hit anyone over the head with a message. I wanted to say something about making stuff instead of consuming stuff.

And I wanted to have fun. And if I did it right and didn’t plan too much that fun would come across on the screen…the small screen, most likely. As I put scenes together I found I didn’t need a lot of words. The picture, for the most part, would do the talking, and the music would keep the story moving. It became a silent film with title cards, something I never even considered when I sat down to write the script.

I made five 2 minute episodes and played with putting them together and taking them apart. Music was my inspiration, the music I was using in my film and the music I had listened to most of my life. Rock and Roll. I don’t know if I could have made “Seventy” without Tom Petty. I must have listened to his new “Mudcrutch” song “Trailer,” 1,000 times over two months. I wanted something sweet and simple…

Many images, not always a lot to watch.

The moving image, it seems to me, has become a commodity, like wheat. The creator world has given birth to a billion video creators and trying to find something interesting out there could be like looking for a needle in a haystack. Five hundred hours of video is uploaded to You Tube every minute. You have to be very specific or work very hard and fast to get anyone’s attention for more than five seconds. Vimeo showcases some truly inventive material but you have to be careful, looks can be deceptive. Most short films highlighted on video platforms indeed seem to have a polish and a refinement that only a team of disciplined craftsmen could have created in the past. But that doesn’t necessarily make for art or even a descent three minute video.

That’s what makes the recent explosion of film festivals so exciting. Films at most festivals, it seems, are more carefully curated, often by true aficionados, craftspeople with an artesian bent who can spot original thinking and instinctively separate a true craftsperson from a filmmaker on automatic pilot.

Festivals are where people who know and love film sift through endless entries to carefully, often laboriously cull the kernel from the chaff. And where others, who appreciate the out- of- Hollywood experience, go to sit and watch films. I had always done things for clients or with the idea of making money. Now I want people who have no investment in the product to watch.

Now I only want to make sparks and have fun.

My short film “Seventy” is now on the festival circuit, it recently won Best Picture, Best Director, Best Editing at the Southern Arizona Independent Film Festival and will play at other U.S. Festivals including in the “We Like ’Em Short” Film Festival in Baker City Oregon at the end of August.

Bob Belinoff is an award-winning film-maker, he also writes and speaks about creativity and the creative process. Contact him at bob@digitalwkshop.com. Visit him at https://www.facebook.com/Bobbelinoff/

###

AudNews is the official blog for AudPop.com. AudPop provides filmmakers opportunities to advance their career, a short film library of 10,000+ titles, and a video marketing platform to provide video marketing services for brands, small businesses, nonprofits, studios, and distributors.